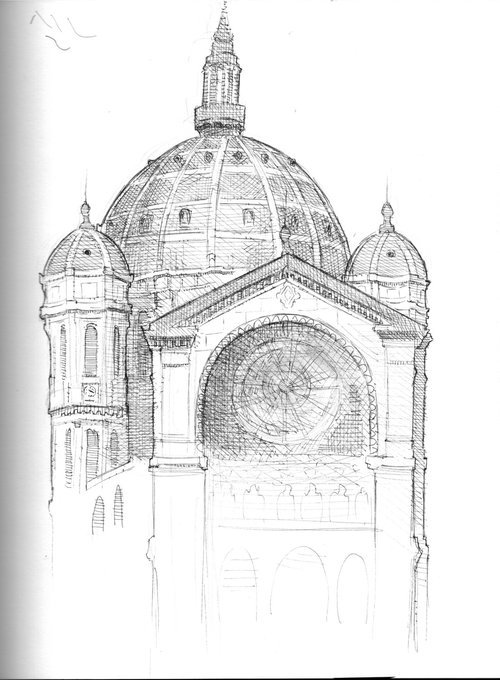

Circular Architectural Study (2023)

He chose architecture for its permanence, the grandeur of a beautiful creation, a perfect marriage of mathematics, engineering, history and art from a mere plot of land.

BY LUAN LI

IMAGE BY CHESLEY DAVIS

I.

To the Architect, every building in the world had a name. And every woman that he encountered in Istanbul, he called Rosalita.

II.

He chose architecture for its permanence, the grandeur of a beautiful creation, a perfect marriage of mathematics, engineering, history, and art from a mere plot of land. Seasons and years may pass, and muses and lovers inevitably vanish into memory, but a magnificent building is eternal. Frank Gehry, Louis Kahn, Norman Foster… such men dreamed in light and concrete, scale and proportion, axes and torques, rails and beams, white and blue.

III.

The Architect smoked his cigarettes and drank his coffee in a coffeehouse late at night in the Karaköy District amidst the college students, artists, photographers, semioticians, theologists, diplomats, and other liars. The coffeehouse was a classical Ottoman construction from the hand of Mimar Sinan. No other architect in this city has surpassed him in four hundred years.

Mimar Sinan lived for almost a century, a man of unusual longevity. While Michelangelo was laying out building plans for Saint Peter’s Basilica, Mimar was sent to the Sultan’s palace in Edirne to apprentice as a carpenter. Mimar Sinan was to the Ottoman East what Michelangelo was to the West.

The Architect spent three months arguing about the elevator design of a hotel with a subcontractor. Time was the only element which separated the two architects, the impossible task of what has already been done and what could be done further.

He refuted that idea that man’s clamber for greatness decreased asymptotically with the passage of time. But he also believed that a man’s architectural philosophy would endure only if driven by a great love and sustained passion, as Shah Jahan commissioning the Taj Mahal.

IV.

She came from a city in Veracruz, a seaport state winding narrowly along the east coast of Mexico. Hot humid beaches lined the sweeping grey coast along the Gulf of Mexico. The city was filled with large colonial squares and wide palm-lined streets, which were once designed for horse-drawn carriages and large lace parasols. That city was flat and charming, its wide boulevards welcoming visitors like open arms. Istanbul was hilly and complex, an endless blaring tangle of markets, mosques, and traffic that evaded the viewers at every turn.

Dérivé is a place of connection and non-connection, where one allows oneself to lose themselves in drifting and to notice what is around them. While on vacation, Rosalita was in a place of permanent dérivé. Istanbul, with its endless alleys and corridors, provided the perfect urban labyrinth to lose oneself in.

Having grown up in the same three-storey house since his birth, dérivé had lost all sense and meaning for the Architect. Dérivé was the place where a woman’s eyebrows almost joined and the chipped red nail polish on her toe.

Squeezing one eye shut, the Architect thrust out his thumb and erected an imaginary tower in their sightline over the apartment buildings. Running down the winding staircase past him, she laughed and told him that he had bad teeth.

Rosalita forced the Architect to chase after her, like a dog chasing a curious passing scent. She liked Istanbul, and the Architect liked her for the same reason: the romance of not knowing.

V.

He needed perfection like he needed cigarettes and Turkish coffee, or the sensuous curves of a woman. All lines fell into place, all one hundred and seven columns of the Hagia Sophia reaching up into the vast, immaculate dome. Gold tendrils creeped along the surfaces of minarets, the blue tulips of the Iznik tiles, the voluminous curves of carved marble of the Mihrab. All patterns faithfully repeated ad infinitum, reaching from ground to ceiling, then into the sky.

In the cutthroat world of high-end architects, the error of a millimeter was the death knell to a career. At the drafting table, his arm and wrist swivelled with controlled precision, cigarette after cigarette, lightbulb after lightbulb, hour after hour. Night after night, having channeled that mysterious compulsion until even the stray cats fell asleep, he collapsed in exhaustion on his rattan sofa.

Antoni Gaudi once said that the straight line belongs to Man, but the curved line belongs to God.

VI.

The Basilica Cistern was built during the age of the Byzantines under Emperor Justinian I, under the surface of modern-day Istanbul. Tears of slaves were carved into the columns of the Basilica Cistern. The architect wanted to be a teardrop in history.

He wanted to fuse his philosophy into a building so that Rosalita’s descendants could stand on the conveyor walkways and look up into the vaulted ceilings of an airport terminal, as natural light beamed on their luggage and their tired, cross-continental faces. He would welcome them with the first immersive, aesthetic experience of Istanbul, the grand passage from West to East.

The Architect believed there was nothing better than to be survived by a building. Rosalita was the altar to immortality, and his life’s work was its marble steps.

Each intricate portico or gleaming façade loomed overhead, waiting to be noticed by the people below. In the mausoleum hall, children ran past old men, mothers clutched baskets and handkerchiefs, and the janitor swept the marble floor. But one day, standing in the crowded line, a woman would suddenly be moved to tears, watching the sun shoot an obelisk through the stained-glass window.

Everything in his life was meticulously placed in servitude to this woman, whose curves were made by God. The sofa was minimalist and gray, the tables were transparent, and his bedding was white and blue.

VII.

Mimar Sinan, our carpenter-turned-civil-engineer-turned-architect, took issue with the fact that no one believed that any architect in the empire could produce a dome as vast and deep as the Sophia Hagia, so he built the dome of the Selimiye Mosque, in the old capital of Edirne, to be both six yards taller and four yards deeper. At age eighty-four, he had accomplished the greatest feat of the classical Ottoman period.

As the Grand Architect of Istanbul, the Mimar produced over four hundred buildings in his name by copying the frameworks and patterns from his catalogue of Istanbul elements, faithfully adhering to the rigid rules of the Sultan.

Talented architects and breathtaking designs surfaced over the centuries, but what remained etched in the world’s aesthetic recognition of Istanbul was Mimar’s catalogue, endlessly reproduced, repeated, and reinforced throughout the empire. What endured was the easily reproducible.

VIII.

The Architect habitually picked up nameless women and made love to them on Friday nights. Having chosen his life of servitude, he was unable to entertain earthly relationships with other women. Compromising on matters of taste, sharing a refrigerator, going on weekend trips, spending money on expensive shoes, entertaining in-laws, squabbling over children, only delayed his ability to reach perfection. To him, they could have been any one or the other, merely reproducible copies of Rosalita.

On one such night, in his final throes of passion, he suddenly stopped, catching a glimpse of his reflection in the closet mirror. Jagged creases lined his mouth, replacing the smooth complexion of youth with a sombre marble façade.

The girl he picked up, a young student, threw him off. She did not want to catch his mortality like a cold.

Rosalita’s frame hung in the hallway of his mind, the copper glow of her face like the Virgin Mary. Three red tears dotted her cheek like wine drops, and he chased after her visage through the shadowy corridors and down the winding steps. Out on the rain-soaked street, a honk from an oncoming truck made him jump in his disheveled pyjamas.

To his left and right, teenage boys sold SIM cards in booths, and old men sold balloons on bicycles.

IX.

The Architect embarked on the last night ferry along the Bosphorus. After countless rounds of arak and then quelled by three cups of black coffee, he pulled out his white pill bottle from his pant pocket and washed the pills down: one for aching joints, two for acid reflux, three for the malady of time.

The Architect coughed at a gust of strong wind and clambered to sit down. To his left and right were old men in wool caps, old men with oily black fingers and ugly shoes. They casually ignored the Architect’s coughing and made room for him. Clutching the rail as he tugged at the grey of his temple, the Architect wondered who could be there to rescue these old men who had nothing to show for; no binding principle, no structural cohesion, no grand design.

They’ve never placed undulating sea waves on the ceiling of a grand train station for the future generations of the world or designed the criss-cross light beams of an opera hall for a beautiful Mexican woman in a ball gown. They’ve never entered the dreams of other people, much less designed the spatial and aesthetic experiences, the structure of dreams for other people to enter. These grey-haired men, balding men, were buried in yesterday’s headlines, lottery tickets, sanctimony, old pornography, Heidegger’s Being and Time, handkerchiefs, the construction of tulips, tobacco, and prayer beads.

The Architect took a shaky gulp of water. He may have been lonely, but he had his great love and sustained passion, which would transcend into the greatest architectural feat of the century. What did they have? Out of their pants pockets, only gobs of candy to give to grandchildren.

The lights of the city on the hill refracted across the black water like gold sand. A gust of wind blew away the Architect’s cap, and he let out a cry, helplessly watching it disappear over the white railing and into the waves. Along Istanbul’s Haliç waterway, Mimar’s minarets shifted provocatively in and out of view, their foggy silhouettes like a distant taunt.

Luan Li is a student in the Humber Creative Writing Post-Graduate Program. Based in Vancouver, BC, she is working on a forthcoming novel which was shortlisted for the JCW Emerging Writer's Prize in 2020. She is interested in telling stories which collide at the intersection of aesthetics, identity, and longing.

Image: Circular Architectural Study (Chesley Davis, 2023)

Edited for publication by Mary Hamilton as part of the Creative Book Publishing program.

HLR Spotlight is a collaboration between the Faculty of Media & Creative Arts and the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and Innovative Learning at Humber College in Toronto, Ontario. This project is funded by Humber’s Office of Research & Innovation and the Faculty of Media & Creative Arts.